Interviews 2025 (49-56):

Trivedi, Geolingo, Siken, Yebio

The Shore Interview #49: Disha Trivedi

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: Your poem, “Martha’s Vineyard,” clearly hinges on ruminations of witnessing wealth in its titular location. But while the poem opens on this image, it does not end on it, but seemingly goes beyond it. How do you see this contrast adding meaningful “ripples” to the poem’s surface level concerns?

DT: The poem ends on this “ship of salt and air.” That’s not very substantial. Poetry isn’t either, but we write it, we read it, we need it. Maybe a poem is a ship, an end, an escape. In “a ship of salt and air,” there exists the possibility of nourishment. Salt is so important to the balance of our body’s chemistry and we need air to breathe, but it’s still just salt, just air. It’s not a ship that holds much weight, but it doesn’t need to. It’s like the pixie-dusted Peter Pan ship crossing the night sky—an unlikely possibility that’s nice to believe in. And maybe that’s enough.

EF: Color is highlighted throughout your poem, from images of the speaker’s “brown face,” to their peers as “gold children,” that are “marked” by the island’s “white sails” and “white linens.” The poem goes further, though, complicating these initial colors with “striper” fish and a “silent fishing line…invisible but motion / tugging” and how the poem points to these invisible lines that imply the connectivity of all the poem’s subjects. Can you speak to your process of meaningfully balancing this interplay of color and is there a “color” image you are surprised ended up in your poem’s palate?

DT: It's hard to speak about my process as intentional because my first drafts aren’t very intentional. My poems begin as subconscious image sequences, like a half-remembered film that I’m writing down. Line breaks are like jump cuts, flashbacks intercede, words are sort of actors. I draft poems based on how those images appear and how words sound when I describe them. The colors come from what’s present in those images.

I keep a good record of drafts, so I looked back at the first draft of this poem (which was not titled “Martha’s Vineyard”). “Salmon” was present twice. As were “white pants” and “white marina” and “non-white face,” though none of those descriptions are in the final version. “Brown” took a few drafts to appear. The speaker doesn’t really want to show her face, especially in a place, or poem, where “brown” doesn’t seem to belong.

“Salmon” feels like it catches the color of New England. Salmon shorts and salmon dinners and salmon sunrise over the ocean. I’m not surprised that color persisted through my drafts. I am surprised that I didn’t write about the ocean, which is very color-rich. The poem circles the idea of the ocean, with reference to salt, water, ripples, stripers, sails. I’m curious why I omitted a description of the ocean, but I like that I did. The poem is grounded on the island. Marooned, maybe, in its lines. The New England that I know is a place of lines—hidden, imagined, material and sometimes magical, if we’re lucky, or if we can afford the price.

EF: I am fascinated by the implications of the moment where the “I” of the poem is at a pizza place and explains how “one man stares at me / so deeply I can’t tell whether to be / concerned.” The enjambment on “whether to be” suggests this momentary existential crisis for the “I”, emphasizing the “concern” in the following line more than passing humor or awkward interaction, but perhaps a deeper concern of self-perception. As a physical location, and as a human interaction, what felt vital about writing toward this moment in the poem and its centrality to a poem about Martha’s Vineyard?

DT: I wrote the first draft of this poem a few years ago during a sailboat race at Martha’s Vineyard, the first large race that I’d done. That was a week of salt spray and sprained ankles and sails lifted in changing wind. At night, I fell asleep on the sailboat’s deck, under a blanket of marine fog, feeling the tide shifting beneath me.

That week felt too charmed to be real.

At the race reception with the sailing team I’d crewed with, I looked around at the attendees, other sailors, all haloed by the golden hour, and looking broke the spell: I was the only non-staff person of color present at the party. Then a man as golden as the hour stood up and gave a speech that started with this sentence: “Sailing is a dying sport.” He went on to discuss methods to resuscitate it.

One method that he mentioned is to make sailing more accessible to people who look less like him and more like me. That’s easier said than done. Sailing is a world that is very much about who you know, how they know you, how you get along. I’m a brown girl who picked up sailing in her early twenties while pursuing higher education at an institution with a robust sailing program. I’m not who you might expect to be a sailor, but I love it anyway. I love the grit of salt between my palms and ropes, the days of sun and water, the self-reliance the sport requires, even in a community of sailors who welcomed me into this strange, exclusive world. I love everything about sailing except that exclusivity.

This poem came out of writing into the dissonance of feeling at home out on the ocean and out of place on the island. The poem is caught in the middle distance, under the sails that flocked the Vineyard’s waters for the duration of my time there.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you're currently enjoying?

DT: A friend sent me the latest issue from Occulum and there’s a lot I love about it, like Helen Victoria Murray’s poem “Prometheus waits for the eagle to text him back.” Rattle is a mainstay, especially their “Poets Respond” series. Other places that I read include Maudlin House, Broken Antler, body fluids, Rust & Moth and wildness. Recently, three writer friends and I co-founded a literary magazine, M E N A C E—a space for modern gothic horror and the “literary weird.” We’re actively seeking poetry submissions for our summer issue.

I’m also in a workshop with Sam Cha about long poems, so lately I’ve been reading more poetry collections to understand how poets arrange a set of poems or a long poem. Jimin Seo’s OSSIA has been on my shelf for months; now that I’m finally getting around to it, it’s unlike anything I’ve ever read. Musical, tactile, eerie. And so beautifully designed. Other collections that I’ve recently enjoyed include Good Monster by Diannely Antigua, savings time by Roya Marsh and Return by Emily Lee Luan.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

DT: I love how this question sent me on a quest to close-read the poems in this issue. Here’s two poems who explore science, hope, and loss through wildly different forms: Elizabeth Wing’s “Rasputin asks for a second cup of wine” and Ellis Purdie’s “Elegy for a Biologist.”

“Elegy for a Biologist” works in compact paragraphs that mirror their subject matter—the eponymous biologist’s “work of honoring carcass.” Grief, like a carcass, is “a specimen too broken to keep.” Yet the speaker suggests that when a loved one dies, the entropy of grief can be ordered in a way that borrows from scientific order, which categorizes death and its disintegration. In the poem, the speaker finds meaning in the mess of grief by condensing grief into a series of keepsakes sent into the afterlife with loved ones, and finally, with the speaker themselves. Through these objects, the poem asks, what do we bring to death and beyond? What do we hope would persist beyond death? For the speaker, the hope is that love persists, in the form of “the gray fox skull I would cradle / in the crook of my arm, hold my hand / and hand to you, should we wake again.”

In contrast to the order that defines “Elegy,” “Rasputin asks for a second cup of wine” breaks form, with lines and phrases that leap across the page in the same way that the speaker, who I read to be an adult revisiting their memory of childhood, would do. Much like “Elegy,” the poem ends with a direct second-person address that holds both finality and hope. While “Elegy” uses science to process the death of beloveds, “Rasputin” uses science to frame the death of innocence, the death of the idea of infinite knowledge and infinite selves, as the speaker admits a variety of magical yet scientific occupations: “Sometimes I said I could make the blood clot . . . Or an egg yolk examiner / or the one they bring in to keep the heart pumping when they cut a / man open, / or the one who studies the sun.”

The next line is both devastating and resigned: “But it is a fact that I am a child up after bedtime. / Please. I am eavesdropping in the hallway.” The speaker seeks to be let into the dizzy world of wine-tinged knowledge yet knows that knowledge strips away the infinite possibility of imagination and the innocence that accompanied that childlike sense of possibility.

Through forms that diverge as much as their subjects converge, both poems explore the containment and curiosity that science offers to make sense of grief, whether the grief that follows the death of loved ones or the grief that comes from growing up.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Disha Trivedi is from Northern California. Her poetry and fiction appears in Rust & Moth, Rogue Agent, The Women's Issue anthology from The Harvard Advocate and elsewhere. She lives in New York City.

________________________________________________________________________________________

The Shore Interview #50: Jaiden Geolingo

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: When I first read your poems, “Boyhood Requiem” and “Contrapuntal for My Dead Loves,” I found myself taken by how they lent themselves to being put in conversation with one another. In fact, they seem to compliment one another because of the different stakes they have. What can you tell us about the way you see these two pieces working together and perhaps in a larger project of yours?

JD: Thank you so much for having me! Both of these pieces emerged from the notion of displacement. “Contrapuntal for My Dead Love” was a letter to the South and how it affected the things in my life, both through personal growth and through the accompanying environment. “Boyhood Requiem” resulted from an observation in the South: I noticed that the people around me categorized masculinity through interests: what cologne you wear, what songs you listen to, or what kind of life you lead in general. Both poems, to me, are intertwined in that theme of disorganization and alienation and they’re told by a speaker who is constantly in this space of disorder. I’m glad that you agree they compliment each other! While I don’t think they’re in direct conversation, I know they stemmed from the same corner.

EF: With the three readings of “Contrapuntal for My Dead Loves,” how do you see each “I” inhabiting each reading as distinct from one other? And what felt urgent about these three readings that you turned to this form?

JD: “Contrapuntal for My Dead Loves” came from a moment in my life where I wanted to communicate with the ground I step on. In this piece, my “dead love” is not a singular subject; it expands into a larger scale—into a geographical area like the South that has been a large part of my life. Before writing this, I already had the concept of writing a contrapuntal in mind; although, unraveling the intent behind this form is what stumped me during the first round of creation. Initially, I wanted to focus on a singular Southern experience—such as the floods and hurricanes—and then tie it into a larger symbol. However, I had an innate feeling that told me to derail from everything and erase the linearity; eventually, it became abstract and an amalgamation of the South and I, split into two perspectives.

I never grew up in the South. I lived in the Philippines my whole life until I migrated to the United States around three years ago—and due to that assimilation, discovering what the South was like from a foreign eye grew to be a more foreign feeling than the immigration process. This played a part in the “splitting” within the form: my identity in this region was never solidified. On the left hand side of the poem, I am talking to a phantom: someone to pour my thoughts into—and I exposed my want to them. The “I” in this section refers to me, the writer and the crescendoing emotions I wanted to express about this region.

And yet, on the right hand side, the “I” is the South itself. With each line, the South retaliates, aware of their roughness, told through lines like “enter & I, a dead love, will turn into wolves.” I intended to personify the South as well because I believed that the splitting of the contrapuntal would be redundant without a contrasting element—in this case, the subject of the poem. These two segments differed in the speaker and, ultimately, will contribute to the merging of the sections.

The unification of both voices was rough to say the least. Like I said earlier, both sections were told through me and through the South. However, combining those perspectives was both exasperating and fulfilling. Instead of turning into a singular reading with no meaning, it became more of a conversation between the South and I—a soft understanding of both perceptions that I wanted to depict through lines like “I autopsy your teeth & I find prayers made of alcohol / I want to confess my mouth outward.” There’s no animosity to the South to me. We’re cordial, as much as I want to leave and return to my home country. I still love it. It’s still a home.

EF: In “Boyhood Requiem,” there are four single word, alliterative lines: “cologne,” “carmine,” “cliché” and “circuiting.” With the form of the poem clearly emphasizing these words, can you speak to what your drafting process that brought you to this current form, and in particular, these aligned words?

JD: Boyhood Requiem was a thrilling piece to write. It arose from being surrounded in an environment where people tend to notate “masculinity” through their interests and niches. Therefore, I structured the poem to be sporadic, stretching across the page to symbolize the rupture from societal expectations. I wanted these four words to radiate in a way that reflects the theme of the poem, so thank you for noticing that!

If you separate these words into a unified concept, they actually begin to converge into a list that recurs to the theme of toxic masculinity. Firstly, cologne as a symbol originated from the ideology that fragrance is the makeup counterpart to men, and that the scent you bore placed you in a hierarchy (which isn’t entirely true; I watched a video about this topic a few months ago, but I can’t remember the title for the life of me). Furthermore, I wanted carmine to mimic the hue of blood. I often think back to Ocean Vuong’s interview on Late Night with Seth Meyers, where he discusses the usage of a lexicon of violence in regards to masculinity. Harnessing that idea, I aimed to emphasize the violence that comes with masculinity through the word carmine.

Cliché and circuiting became more contradictory in terms of word choice. When the former set discussed the elements that come with masculinity, the latter discussed the elements involved in evading that standard—in simpler terms, cliché and circuiting became an outlet to criticize the Masculine-Complex. There’s a reason why people associate masculinity with toxicity (i.e., the term toxic masculinity); as I mentioned earlier, people categorize masculine behavior with superficiality: the things they possess, the things they wear, what music they listen to, etc. It’s cliché. Circuiting had a similar message: I wanted to convey the need most men possess in rewiring their personality and circuitry to conform with social trends; however, I also wanted to convey how they rewire themselves to step out of these trends.

Masculinity isn’t shameful. Individuality isn’t shameful. There’s still a delicate tenderness in not caring about what others think. That’s what I want people to gain from Boyhood Requiem. We’re all “still men / and still animals.”

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you’re currently enjoying?

JD: Yes! Currently, my favorite journal to read through is The Adroit Journal. Each piece in their issues deviates from the conventional literary magazine poem; instead of flowering imagery and an elegant undertone to rhythm, these pieces are more conversational and aggressive. They feel like car crashes or meteor strikes, or the feeling when your breath hitches once you run out of stamina. Ultimately, it feels hypnotic. When I first began writing poetry about a year ago, I always told myself that poetry is made up of verbose and metaphor-threaded words; however, reading more and more allowed me to unravel that poetry came down to the emotional invocation. The Adroit Journal became a reminder to me that beauty through words can come from simplicity.

A few honorable mentions are Rust + Moth, diode, Tinderbox Poetry Journal and POETRY!

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

JD: I love this question so much! To me, two poems that converse the best with each other are Beth Oast William’s “What Wood We’ve Become” and Le Wang’s “Hunting Season.” This is completely up to my interpretation, so take my insight with a grain of salt.

These poems address the intimacy of survival and violence, both thematically and stylistically. William’s poem involves her metaphorical transformation into instability in the aftermath of survival (the wood as a metaphor for something immobile, or something numb). This piece is littered with the diction of recovery, like the line “whatever it is we do / mid-dream to reset the clock”—which I interpreted as the stage of denial. In this poem, we are shown a constant aftermath after a significant event.

“Hunting Season” became more of the antithesis of “What Wood We’ve Become.” Instead of the yearning for survival, we are shown the theme of violence, told through the eyes of hunters in a paternal space. However, in a way, the speaker in “Hunting Season” inevitably learns what survival is through the violence. The father in this poem converses with his child, informing them about the delicacy of violence, how they “make a fortune off / dying things”. At first read, I didn’t see a connection between Wang’s and William’s poems; however, as I kept thinking about the violence that lingered between them—and the desperation of life (whether that be your own or another’s) seeping between each line, a linear string threaded them together. Additionally, aside from thematics, I noticed a similarity in both poet’s styles. Implementing mirroring images of brutality and nature, a link formed once I realized how each poet’s flow remained the same; as opposed to the standardized, abrupt flow that tends to come with violent poems, both of these pieces remained slow and unnerving. With each read, they grew to be more confessional than I realized and that is what I believe was the first connection that led me to these two becoming my pick. I loved reading all the poems in this issue so much! And, once again, thank you so much for having me. I’m truly honored.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Jaiden Geolingo is a Pinoy writer based in Georgia, United States. He has been publicly recognized by The National YoungArts Foundation, The Scholastic Art & Writing Awards, Young Poets Network, among others. Additionally, his work can be found published or forthcoming in Dishsoap Quarterly, The Poetry Society, eunoia and other journals. Someday, he will be good at math.

Jaiden Geolingo

The Shore Interview #51: Richard Siken

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: In “Fauna” there’s a presence of location and place, whether it’s a deer caught in something, the end of the world in LA, or the sign and the beach; and in “Strata” the “flat nastiness of Nebraska,” the Badlands of South Dakota, landfills and the side of the road. Then, there’s “Volta,” its titular turning, away and towards, is seemingly placeless, dislocated. How do you see movement, place, location, or lack thereof, working in this current collection of work?

RS: I think the whole collection is an attempt to locate a self. The poems in I Do Know Some Things show greater or lesser degrees of surety, starting with the experience of the stroke itself: I went back and locked the door and stood in front of the house to wait for my friend but I wasn’t standing in front of the house, I was lying on the sidewalk with my face in my shoulder bag because I couldn’t stand up… And then, in the hospital bed, there’s this: I swear to god, there must have been a day on the beach or a secret dip in the lake after dinner. I must have walked all night against the wind once, trying to get somewhere. There must have been. “Fauna” and “Strata” are in the final section of the book. By then, I’ve regained some sense of location and place. I think that’s the real recovery. Walking again is great, but being able to locate myself in the world was crucial.

EF: You’ve previously talked about the writing process of your forthcoming collection, including mentioning a process of writing out a piece then erasing bit by bit to its essence. What I’m curious about is if you could speak to your process of arranging I Do Know Some Things on a collection level, did you similarly use a process of excision, or were there gaps to fill?

RS: In the hospital, I made a list of terms I needed to understand—bed, floor, meat, noon—to see if I could find landmarks for meaning. It turned into a glossary, then a compilation of encyclopedia entries. My whole life was a gap to fill. I figured I’d start with the nouns and see if I could connect them. My understanding of the words led to stories or meditations on the words. The book accumulated around the words. The erasing happened in the rewrites. There were too many false leads, distractions and tangential ideas that strayed away from the the initial concern—the word—that just muddied up the thinking and the goal.

Looking at the table of contents, it’s odd that I chose these 77 terms to describe my life. I never expected that beet soup, cult leader and heart valve would be foundational. There were some words I had to add towards the end—true love, poetry—because those are fundamental also. But those were obvious choices.

The book moves forward in two ways. It follows my stroke and the aftermath chronologically, and around those moments are poems that are related by theme. The issues I was confronting in my recovery would remind me of other times I had confronted similar issues. “Fauna” was concerned with the idea that I might not fully recover. “Strata” was an attempt to look at the construction of the book and its layers as a strange accumulation of historical fact.

EF: When the friction of the sentence against the line is absent, is there something in its stead that you think a reader encounters when approaching prose as poetry that still creates that friction in other ways? Or do you consider there to be other tensions at work?

RS: Breaking a line makes a powerful friction between the unit of the sentence and the unit of the line. You lose a lot when you decline to use it. I wasn’t able to break the line. Everything was so disconnected it didn’t make sense to break anything when I was trying so hard to stitch everything back together. I think the power of the poems comes in the spaces between the sentences. To use associative leaps is a craft choice, but it’s also a representation of how I was thinking, how I’m still thinking. Everything jumps around. I take the long way around to get to meaning. The recovery from a brain injury isn’t focused on healing the damaged area, it’s focused on growing new neural pathways around the damaged area. My thinking, my language, goes around the damaged areas. It circles lost memories and gaps in logic. I think the actual experience of my recovery is the actual poetry of it.

EF: What have you been reading lately that influences your work or thinking?

RS: I asked for a replacement question and got this one, which concerns the same thing. When you ask a question, you have to be prepared for the possible answers. When faced with an uncomfortable question, you have the choices of answering, lying, or deflecting. You are giving me an opportunity to pull you into my private world, which is something I rarely do. Complicating that is the fact that I can’t read yet. Not without great difficulty. I don’t like admitting it. I can’t follow and I can’t track. If it’s longer than a page, I have to reread it many times. To understand the basics, I have to take notes. I’m pretty good with conversation, but with poems and stories I’m at a loss.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

RS: I think this is a great question. I think you should ask this question of everyone. Answering it is beyond my current skill set. I have successfully defined some words and made some paragraphs. That’s the book I have. That’s all I have. I still get lost in the supermarket. I still blank out when asked simple questions. I smile a lot because that makes people happy but I am hiding as much of my damage as I can. I still have a long way to go.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Richard Siken is a poet and painter. His book Crush won the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, selected by Louise Glück, a Lambda Literary Award, a Thom Gunn Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other books are War of the Foxes (Copper Canyon Press, 2015) and I Do Know Some Things (forthcoming, Copper Canyon Press, 2025). Siken is a recipient of fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

Richard Siken

The Shore Interview #52: Yishak Yohannes Yebio

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: Hi Yishak, what immediately drew me to your work were the different ways each of your respective poems deals with the past. In “Theory of Falling,” the “I” reckons with being told they were “born in the wrong century,” and hearing “not the Earth’s heartbeat / but the sound of graves shifting.” The poem predominantly responds grammatically, by shifting into hypothetical “if I could, I would” modals, then future tense, before settling back into the present. “The Walk Home,” on the other hand, responds to the past more formally, switching from tercet stanzas, to alternating couplets and quatrains, only switching fully to past tense in the final stanza. Reading them now, how does the idea of time play with the known and unknown in your poems?

YYY: In both poems, time isn’t a fixed backdrop. It’s something the speaker is actively negotiating, testing and rethreading to make sense of what can be held and what can’t.

In “Theory of Falling,” the hypothetical modals (“if I could, I would…”) open a speculative space that tries to rewrite inherited realities—war, violence, displacement—into something gentler. The movement into future tense feels like a reach toward an imagined survivability, even if it can’t be fully realized. By the poem’s end, returning to the present is less a resolution than an acknowledgment that the unknown (what could have been, what could still be) will always run parallel to the known (what is).

In “The Walk Home,” time shifts less in grammar than in architecture. The change in stanza form enacts a kind of spatial rearranging, like memory inserting itself into the present moment. The past enters slowly through sensory triggers (the smell of citrus, the sound of collisions) until, in the final stanza, the verb tense fully concedes to it. Here, the unknown isn’t a speculative future but the fluid, unstable nature of memory itself, emblematic of how we can never be sure when it will surface or what it will demand from us.

In both, the known is tactile and immediate, while the unknown hovers in temporal shifts: a century one wasn’t meant for, a childhood afternoon reappearing decades later. Time becomes a medium that blurs the edges between them, making the poems less about chronology and more about permeability. How our past, present and imagined futures keep slipping into each other.

EF: In “The Walk Home,” there is a constant domesticity that the poem revolves around. Many images cycle through the senses, with multiple using synesthesia, like my favorite one: “talc-sweet hush.” What role do you see the domestic space playing in this poem, or in your work more broadly? And are there unconventional spaces or situations that also conjure this “domesticity” for you?

YYY: In “The Walk Home,” the domestic space acts less as a static setting and more as a vessel for holding fragments of time. The kitchen, the smell of citrus, the clatter of dishes—all of these become not just background, but active participants in the poem’s associative movement. Domesticity here is a kind of anchor: it allows the speaker to move between the now and remembered past without losing their footing. It’s a tactile, sensory framework that can absorb both quiet intimacy and sudden memory.

More broadly in my work, domesticity isn’t only tied to the literal home. It’s any space where the body can briefly exhale, where the senses are allowed to arrange the world in familiar patterns. Sometimes that’s a kitchen table; other times it’s a bus seat, a public library aisle, or a friend’s porch at dusk. I find domesticity in moments of shared ritual. The snapping green beans with a relative, mending a shirt in silence, walking home with groceries, whether they happen in a private room or in the middle of a crowded street.

Unconventional “domestic” spaces often surface in my poems as places where care is improvised: like a temporary shelter made of conversation. They’re not always safe, but they are places where the self can briefly locate itself—much like in “The Walk Home,” where the scent of cut fruit stitches disparate afternoons together into a single, livable moment.

EF: I keep finding myself drawn to the title, “Theory of Falling,” for its multi-faceted potency, especially in how it can be applied to individual lines, stanzas, or the whole poem, in multiple ways. Could you tell us some of your favorite applications of this title to specific instances or threads within the poem?

YYY: I love that you noticed how “Theory of Falling” can refract differently depending on where you hold it in the poem. For me, the title works almost like a gravitational field—it keeps pulling different images and gestures into its orbit. The title becomes a prism: falling as violence, as memory, as surrender, as descent into grief, but also as the very motion that allows renewal. It’s less a single “theory” than a set of possibilities the poem keeps testing.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you’re currently enjoying?

YYY: I’m really enjoying the Nowhere Girl Collective and Frontier Poetry. They’re both great places to read contemporary poetry and they spotlight both up-and-coming and established writers.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

YYY: I really enjoyed Yan Zhang’s “Ars Poetica” and Bethany Schultz Hurst's “Letter to Geppetto, Written on the Back of a Red Lobster Menu.” What struck me in reading these two poems together is how both are wrestling with containment and collapse, though they approach it differently. “Letter to Geppetto” filters that experience through cultural ruin, finding a strange home in the belly of the whale, the mall, the failing Red Lobster—while the street poem is more rooted in close perception, watching how sunlight, dumpsters, and cicadas slip in and out of memory. One leans toward allegory, the other toward meditation, but both ask the same question: how do we live meaningfully inside wreckage, and what does it take to translate the fleeting or the broken into something that lasts?

________________________________________________________________________________________

Yishak Yohannes Yebio was the 2024 Youth Poet Laureate of Washington D.C. and the Arts and Social Justice Fellow at the Strathmore and Wooly Mammoth Theatre. His work has been featured or is forthcoming in Eunoia Review, Nowhere Girl Collective, Inflectionist Review, Delta Poetry Review and elsewhere.

Yishak Yohannes Yebio

The Shore Interview #53: Jane Zwart

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: Hi Jane, it’s an honor getting to interview you so close to your first collection coming out. Can you tell us a little about the creative journey this collection went on before its current state it’s about to be published in? I’m curious to know a little bit about your process of arranging your collection as a manuscript. Are your poems that appear in our issues a part of this collection?

JZ: Hello–and thank you, Ella, for inviting me into conversation. It means all the more because I’m so grateful to the crew at The Shore already. You all have introduced me to so many poems I’ve loved and for you’ve also been so kind to me and my poems. And there are poems I first published in The Shore in the manuscript I’m trying in open reading periods and manuscript contests now. But not in Oddest & Oldest & Saddest & Best, which will come out in February with Orison Books.

Your question about arranging those poems is a good one, and it was undoubtedly a process wrangling into a book what was, to begin, a stack of poems that 1) I thought were keepers and 2) felt like they belonged to the same extended family or ecosystem. Only part of the process was mine, though. Along the way, I leaned a great deal on my poetry kin: W.J. Herbert gave me what I would describe as a master class in sequencing poems, Christian Wiman helped me do some important weeding and transplanting, and Luke Hankins urged me to think of the book as a triptych.

One of the memories that kept coming back to me as I worked on arranging the book was of making mix tapes in high school and college because the goals seem analogous: in a play list, you want enough connecting threads and you want some surprises. But I kept remembering, too, my high school art teacher, Gwen Potts, talking about the color wheel and specifically about how sometimes colors suit each other because they’re neighbors and sometimes because they’re opposites. Within each one of the book’s three parts, I wanted to have some of both kinds of relationships: proximities and rivalries. But, as Mrs. Potts would tell you, painters also use color in triads (imagine where the vertices of an isosceles triangle would land if you imposed it on the color wheel) and the relationship between the book’s three parts feels to me more like that.

EF: Your two poems, “Folding” and “Pink,” seem quite stylistically different on the surface and yet when read in conjunction, I was struck by their shared sense of, what I can only approximate as, urgent contemplation. The “I” in “Folding” differentiates people witnessing the tearing down of a Texas Roadhouse from those who continue to “lower groceries into cars’ trunks,” while the lens of the poem suggests the “I” falls into the category of the former, the “I” never definitively places itself in either, leaving the “I” in a tenuous liminality. In “Pink,” the “I” only emerges in the second stanza and is surrounded with conditionals, like the “as if”s in the first stanza and the “just in time” of the last. Have there been surprising instances that sparked this urgent contemplation, whether it was in a place or moment you didn’t expect?

JZ: “Urgent contemplation” is such a great phrase and I think you’re right about that cagey “I” as well. In “Folding,” the “I” is noncommittal and hides out in a two-part “us.” In “Pink,” the “I” sneaks into the poem from the past and then ducks back out of sight, turning the third stanza over to the rebukes it lists without explicitly claiming them as rebukes to herself. I suppose that unsettledness in the poems’ speakers has to do with the fact that whatever urgency they hold, it does have to do with contemplation, with taking something in, with perceiving it truthfully—much more than with reaching a decision.

Maybe part of what’s happening in those poems, too, is that the self’s urgent need to contemplate something outside herself crowds out the need to distinguish herself. In writing these poems, what felt pressing had very little to do with me. I didn’t need to take sides. I didn’t need to arrive at a conclusion. I only needed to bear witness to an Outback Steakhouse being demolished, in the one case and, in the other, I only needed to survey the contradictions inside a color. The “I” whose job that kind of thing is matters mostly for the attention she can pay. Her personality, for the length of the poem, doesn’t hold a candle to her perception.

EF: As a teacher of literature and writing, I’m sure to some extent there’s a reciprocal influence from your students on your work. Could you share some ways your work as a teacher has influenced either “Folding,” “Pink,” or your forthcoming collection?

JZ: There is so much reciprocity in teaching and learning, which, as far as the perks of my job go, I’d put near the top of the list. So much of influence, though, is invisible—so I’m not sure how my work teaching literature and writing has left its fingerprints on “Folding” and “Pink.” Not that I’d ever rule it out.

The title poem for my forthcoming collection, however, I know I would never have written were it not for one of my students. He wasn’t, as far as I know, a creative writer, but we were talking after class one day toward the end of the spring semester and I asked him whether he had a summer job lined up. He did, the same job as he worked the previous summer; he was a groundskeeper at a cemetery. I asked him if he liked it and he told me that what surprised him most was how often people who were walking through asked him whether he could point them to the strangest epitaph he’d seen or to the oldest stone in the place or the one that seemed most tragic. Or whether he had a favorite. And that was the seed of “Oddest and Oldest and Saddest and Best.”

Another of the poems in the book I owe to one of the students I taught at Handlon Correctional Facility through the Calvin Prison Initiative. That poem’s heart is something he said in a literature class about Doestoevsky’s Notes from The Underground. Sometimes, though, what I owe one of my students (like what I owe any other writer) is less easy to trace, though I can say that teaching writing I’ve been awed by my students’ daring and generosity again and again, without fail.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you're currently enjoying?

JZ: There are far more than I can list, but in addition to The Shore, Tahoma Literary Review and On the Seawall are two I keep pretty close tabs on. Plume is another online journal I love, and even before Danny Lawless made a spot for me as a co-editor for book reviews, I spent time with it every month. And while I can’t subscribe to nearly as many print journals as I wish I could, I’ve been enjoying Copper Nickel and Cave Wall this fall and I think David Clark has done wonderful things with 32 Poems. I’ll also say that the journal Postcard Lit strikes me as a superb invention; it is true that to receive a set of postcards with poems on them is a tiny bit agonizing—to hoard or to send?—but mainly each issue is a delight.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

JZ: I love this question. Choosing, of course, was another small agony, but two poems in this issue that I adore and can hear conversing are Melody Wilson’s “Singularity” and Mubashira Patel’s “disillusion.” Part of what they have in common is their vast reach: Wilson’s plumbs a black hole, and Patel’s grazes eternity. And part of what they have in common is their magnificent concreteness. “Singularity” describes a black hole as “the nostril of a horse galloping at night;” “disillusion” describes “used toys, faces worn / by the touching.”

Then there are the poems’ smaller serendipities. Both feature fathers and TVs turned on in the evening. And where Patel writes about “loneliness coming in through the drain, / not a scream, not a song— / just the sound water makes / when it doesn’t know where to go,” Wilson tells us that, about a black hole, “they say it’s very still, that it gurgles, // a baby practicing its vowels.”

Most potently, though, both these poems have to do with absence, both absence as a void and absence as avoidance. And Wilson and Patel are wise to absence, how it comes in different weights. Which is probably why each poem ends with a finality that lingers: closure, but closure for someone other than the poems’ speaker.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Jane Zwart teaches at Calvin University and co-edits book reviews for Plume. Her poems have appeared in Poetry, The Southern Review, Threepenny Review, HAD and Ploughshares and her first collection of poems is coming out with Orison Books in February 2026.

Jane Zwart

The Shore Interview #54: Anastasios Mihalopoulos

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: Hi Anastasios, it’s a pleasure getting to conduct this interview with you. I’d like to start off by looking at your poem in our latest issue, “Thoughts on the Invention of the Alphabet from a Cottage in Prince Edward Island.” I keep coming back to the moment in the poem where the form alerts the reader to a disruption in stanza eleven where a tercet is introduced after consistent couplets. Moreover, this disruption creates a visible cause and effect as it leaves the final stanza as a monostich. It’s a beautiful turn in the poem. How do you gauge when a turn feels right for your piece? Do you find it’s a different type of gauging across genres, or do they feel similar?

AM: Hi Ella, the honor is mine! Thank you so much for this generous close read of my work.

I spend a lot of time thinking about the poetic turn both formally and contextually. To refer to the poem specifically, I was thinking a lot about language at the time and I was reading Spell of the Sensuous by David Abram when I wrote it. I’ve been fixated on this idea he suggests that "The written word locks language into fixed forms, stripping it of the fluid, dynamic qualities of speech.” He suggests that "Once the written text began to speak, the voices of the forest and rivers began to fade" (Abram 138). The ideas Abram offers is that by turning to written words for our source of sensuous stimulation we have driven a barrier between ourselves and nature. In this poem, I wanted to echo that idea but also challenge it a bit. I wanted to see if I could use language and line breaks to return to those fluid qualities of nature. So, in my mind, the poem takes both a structural and a contextual turn when it breaks its form with the lone tercet. In that tercet, the focus turns to the negative outcomes of the Anthropocene ( loggers and clear cuts, etc.) before returning to couplets and finally the monostich. My hope is that the turn in both form and content urges the reader to feel a sense of gravity in regard to nature and music, to the idea of compressing all this life and meaning into the note, A.

All of this said, my non-answer to how I gauge when a turn feels right is It depends. There are so many forms a turn can take and so many directions that turn can take us. In some poems, the lack of a turn or climactic reveal becomes a kind of turn itself. In most, cases, I often think of an old scientific adage from biology and chemistry, form determines function. In the case of my poetry, I actually believe that the function of the poem determines the form of verse and the nature of the turn. When I feel those details are aligned that would be when I’d say a turn feels right.

Across genres, I would actually say that the metrics remain the same. While poetry of course can turn via formal aspects of meter, stanza and line breaks, prose requires and relies more on contextual turns, though many prose pieces use forms and shifts in POV to accomplish this.

EF: From the writing workshops you attended in Greece, to your current PhD program in New Brunswick, how do you see the contrast of geographical locations playing out in your work? Do you think it plays a role in your manuscript, Still, Sometimes, Shipwreck?

AM: Absolutely.

I have been fortunate to spend several months in Greece over the years. I attended the Writing Workshops in Greece (WWIG) on the island of Thasos alongside many writers and close friends. This time was especially meaningful to me as a member of the Greek-American Diaspora. I grew up without learning Greek or Italian which led to a sense of cultural disconnection and generated feelings of a lost heritage. These trips continue to function as a kind of reclamation for me.

I’ve always cared deeply about a sense of place and the way natural landscapes influence identity. Still, Sometimes, Shipwreck is very much about this form of home-seeking regarding my Greek and Italian heritage. The poems of this collection often turn to nature and landscape as a means of mending a fractured self with recurring images of broken lighthouses, the sea, my late grandfather and The Odyssey. However, the poems of that collection were written before I moved to Canada. My second manuscript-in-progress, Dancing in the Land of Sound, includes many poems situated in Atlantic Canada as well as in Greece and Italy.

When I first moved to New Brunswick, Canada, I immediately felt a sense of connection. I found a vibrant literary community and a rich tapestry of culture and history that I am continuously striving to learn more about. Soon after moving here, I met my fiancé. Together, we’ve traveled all around Atlantic Canada, often seeking out new, authentic and respectful ways of connecting with the landscape. In this poem and others, it’s evident that these places quickly found their way into my writing.

EF: On top of your creative writing degrees, I found it interesting that you also hold a BS in chemistry. How has studying in the sciences, and chemistry in particular, impacted your creative writing? Could you speak to any occasions in your creative writing career that you found the skills for your chemistry degree came in handy in any surprising way?

AM: I’ve always loved books and science; both for the exploration and sense of discovery that comes with them. When I began my undergraduate degree at Allegheny College I enrolled as a chemistry major and a creative writing minor. It wasn’t until my junior year that I chose to double major in English and Chemistry. It was a moment of recognition that writing would take equal priority in my life. So much of my writing begins with a scientific phenomenon. I think that studying the sciences has certainly impacted my gaze as a poet. I don’t think it’s influenced my writing style as much as it alters where and how I look at things. I actually have a bit of a resistance to using scientific terminology in poems but I love the perspectives one can gain by looking at things through a different lens, from a molecular or an atomic level. That is probably the largest impact the sciences have on me, this altered way of looking at certain phenomena in the world. At the same time, I think that poetry leads me to encounter the sciences differently, to not be so obsessed with “learning” something into oblivion but rather reveling in the unknowability of certain questions. It’s very much a reciprocal relationship.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you're currently enjoying?

AM: I’m always excited for new issues of the Fairy Tale Review. But I’ve read recent work from The Fiddlehead, 32 Poems, Ergon and Ninth Letter to name a few that come to mind.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

AM: I was particularly struck by Michelle Ivy Alwedo’s poem, “By 2050 There Will Be More Plastic in the Sea than Fish,” and Melody Wilson’s “Singularity” and how both works lend a kind of animacy to nonhuman elements. In Alwedo’s poem, “The Atlantic licks the cliffs… with a hunger that startles the old fishermen” and “Even the crows have changed their language” to one of mourning. Here, I see much more than just personification, but a kind of reckoning of what the landscape is telling the reader and the fishermen. Similarly, in Wilson’s poem it is not the black hole but the image of it that takes on the role of nonhuman protagonist. Wilson writes of the photo:

The photo looks a little like everything else,

the ocular lens of a microscope,

the nostril of a horse galloping at night.

They say it’s very still, that it gurgles,

a baby practicing its vowels.

Here, again we understand a form of language, a quiet communication from one being to another like the crows changing their language, the black hole is now practicing its vowels trying to take on another mode of speech to tell us something. What strikes me about both of these poems is how both poets, through careful language and meter, establish a sense of urgency for environmental change by giving voice to the nonhuman world.

________________________________________________________________________________________

Anastasios Mihalopoulos is a Greek/Italian-American from Boardman, Ohio. He received his MFA in poetry from the Northeast Ohio MFA program and his BS in both Chemistry and English from Allegheny College. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Scientific American, Driftwood Press, Fairy Tale Review, Pithead Chapel and elsewhere. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of New Brunswick.

Anastasios Mihalopoulos

The Shore Interview #55: Kevin Clark

Questions by Ella Flores, Interview Editor

EF: It’s a pleasure getting the opportunity to interview you, Kevin. To start off, I’d like to pose an intentionally broad question based on your wide literary citizenship. Between your third full 2022 poetry collection, The Consecrations, and your 1984 and 1990 chapbooks, and of course critical essays throughout, could you speak to how you personally see the concept of literary citizenship having evolved over that period of that time?

KC: I taught for almost two decades at the Rainier Writing Workshop, and one day after one of my reviews had just come out, I was startled when a colleague told me that I was a “good literary citizen.” I was happy to hear such a thing, but I’d never considered the idea per se. Outside of family and friends, my adult life has always been an immersion in literature. For me, this meant writing poetry and criticism, reading poetry voluminously, talking books books books, teaching poetry writing and literature, giving and attending readings and talks, and, later, having the honor of being poet laureate of San Luis Obispo County (CA). I love the ongoing relations I have with so many of my former students. This life remains fun, like a calling or a personal mythos by and in which to live.

When I heard the term “good literary citizen,” it seemed tinged with a kind of responsibility, a charge to do something that you may not always choose to do. But that’s rarely ever been my experience. Since I was a kid, I’ve been enraptured by the way words revealed and enlarged the world. Literature—especially poetry—offers me a way to create an aperture into a small province of what’s heretofore inaccessible. Writing, reading and talking about literature is my good fortune. Literary citizenship for me has been living this privileged life.

EF: And if you’d entertain an additional question, what aspects you’re surprised to be more relevant than ever from your 2007 poetry writing textbook, or what you’d want to add or change in it today?

KC: I wrote The Mind’s Eye: A Guide to Writing Literature (from Pearson Longman) a couple of decades ago and, to my mind, poetic aesthetics haven’t changed that much. The text is still in print. The poems I read in The Shore are not substantially different in aesthetic stance from those I may have seen back then in Ploughshares or The Western Humanities Review.

If I had to cite a section that seems more relevant than ever, I’d have to choose the chapter titled “The Poetry of Witness,” in which I take up political poems. I was always a political person, but I was writing The Mind’s Eye before the MeToo movement and Black Lives Matter and transgender rights and the very real rise of repressive autocratic forces in our country and around the world.

Nevertheless, the textbook holds what I believe are extraordinary poems about racism, sexism, homophobia and other socio-political challenges. In fact, your question sent me back to the book—and I was surprised to see how many political poems are spread throughout, not only in “The Poetry of Witness” chapter. As we know, poets have forever been called to consider injustice as a subject and I’m happy to remember that the book offers so many models of good political poems. I’d be remiss if I didn’t add two things: first, no poet should feel pressured into writing about any subject, and second, too many political poems I read today are preachy or excessively didactic or lacking in imagination. As I say in the The Mind’s Eye, some poets are so filled with rage about an issue that they sacrifice the aesthetic quality of the poem—and thus they may reduce complexity and communicate less effectively.

As to what I may wish to add, while I believe my pedagogical comments all pertain well today, I think I’d include more model poems about the way authoritarian legions restrict our freedoms. In fact, I might include a poem from the current issue of The Shore, Julia C Alter’s poem “Migration Season in Vermont,” which is remarkable in its seamless connections.

I’d also add a section about the way the so-called new sciences can, as a poetic subject, enhance consciousness. Finally, I’d include new comments about online journals and submissions.

EF: I’m in love with the final sentence of “Rue,” quoted here: “How the comic / Bronx plosives of long-gone men in love / with a game and each other return to flood me / despite the would-be shield of my art.” There’s a wonderful interplay between musicality and rhythm that creates so much tension and release in this closing. What are some both trusted and novel veins of musical inspiration you find yourself tapping into to channel this musicality into your work? And has the role it plays in your poetic processing and exploration changed for you much over time?

KC: Well, first off, thanks for your generous comment—and for publishing “Rue.”

I must say, for many years now I’ve enjoyed blending somewhat disparate dictions in a poem. As for inspiration, I’m a big fan of poets such as Lynda Hull and Thylias Moss, that is, those who find ways to include both quotidian dialect and formal expression in a single poem. In the case of “Rue,” I found myself melding slightly elevated diction with that of a more old-time northeast vernacular common to my parents and relatives. I was born in New York City and raised in New Jersey. Though I’ve lived in California for decades, my wife will tell you that my Jersey lingo can return without warning.

When I was writing my second book, Self-Portrait with Expletives, I gained enough confidence to begin mining the old family way of speaking. It’s not something I always turn to in my work, but it’s a melodic option. That way of speaking forms a kind of kindred music in my ear. Exploiting such expression is more intuitive than anything else. In the thousands of micro decisions that go into any one poem, sound is my first determiner. In Jersey talk, there exists a clipped rhythm and an intimating style of stresses, both of which combine to convey myriad shades of emotion. Not long ago, in the journal Raritan, I published a short story, titled “Jersey Sand,” and the narrator tries to describe the ethos behind the speech:

“All the stereotypes—the humped shoulders, the low plosives out of the puckered lips, the jaw pushed forward like a boat’s prow, the feigned surprise with the bulging blood-shot eyes, the voice raised at the bare hint of offense, the rat-a-tat-tat of one syllable words—are you kidding me? It’s honest performance. Says you’ve got the kind of know-how comes from a life stripped of bullshit.”

As seen in innumerable movies and TV shows, I think the inhabitants themselves can get a kick out of their own accent, especially when it’s heightened by faux mockery or one-upmanship or simple raised emotion. Thus, the “plosives” can seem “comic.”

Among other things, I think “Rue” is about the tension between the overwhelming threnodic heartwaves I can feel when thinking of my father and uncle (both of whom died in their forties) and the need to avoid the kind of excess sentimentality that can turn a poem into blubber. I didn’t realize it when I was writing the poem, but now I think the more formal elements of expression (“the taut craft of loss”) render the need to constrain what may seem like childish emotion, while the more vernacular language (“The Globe giving him / the five-finger salute behind a waggish puss / while snatching the one-spot”) mimics the language the three profoundly beloved men would have used themselves, thus making me feel their absence that much more intensely.

As for the last lines you ask about, I’d like to think they are uttered in what I call a falling ghost pentameter. I hope the earlier rhythms of the poem set up the final decrescendo of sound and emotion. Again, such a diminuendo happens due to myriad sensations at the moment of creation, not a mechanistic or conscious series of decisions.

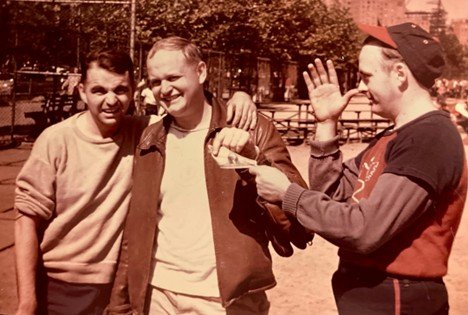

Finally, here’s the photo upon which the poem is based:

Kevin Clark Rue Photograph

EF: Throughout “Fuselage” (and to a lesser degree in “Rue”), there’s a lovely invocation of poetry and/or reference to the poem itself, within the poem. Whether seen as a meta reference, writing about writing, or something else entirely, how and when do you see the inclusion of the poem within the poem as a potent craft choice?

KC: Poems thrive on surprise. Whatever the poet can do to make the reader sit up and take notice can be helpful, right? In theatre and cinema, I’ve always enjoyed the breaking of the fourth wall. I’ve also enjoyed voice-over. (I’m thinking especially of, say, Ferris Buelher’s Day Off and Blade Runner). Breaking from the established narrative can provide an effective strangeness.

In “Fuselage,” the speaker’s fear of flying leads to questions about death—and then to anxieties brought on by certain aspects of postmodern thinking. I know I was reacting against the notion that there’s no such a thing as an author, that the only thing that exists is material, that all beliefs are easily deconstructed. I didn’t realize it as I was writing, but I think such quick associative movements may offer a similar, “potent” strangeness.

The associative jump from a common nervousness about flying to a more disturbing disquiet about the foundational nature of human existence sets up the “poem within the poem.” Matthew Arnold may have called these different loci “actions.” On one hand, the speaker wants to enjoy the altitudinous beauty. He looks forward to seeing his family at home. On the other hand, he’s confronting challenges about the reality of beauty and family. The poem pings back and forth between the two actions. I hope that readers may themselves find a kind of disquieting effect in the alternating, quite oppositional points of view.

EF: Are there any journals or magazines you're currently enjoying?

KC: Funny, but on considering your question, I was surprised to realize how many different journals I can find myself reading at times. Let me note four: When I was in my twenties, The Georgia Review was both very inexpensive and bulging with great literature. I’ve been subscribing since. Though a bit different in taste, over time its four editors—Stan Lindberg, T.R. Hummer, Stephen Corey and Gerald Maa—have maintained exceptionally high standards, so much so that the overall impact never dissipates. I can say the same for The Southern Review, which I’ve read for at least the last twenty-five years or so. Jessica Faust publishes a wide range of poetry that is often remarkably akin to my own preferences. I also enjoy The Threepenny Review, which has some of the most idiosyncratically interesting writing anywhere. Wendy Lesser curates everything from topnotch poetry to photographs to the brilliant miscellany of the Table Talk section. Finally, let me put a good word in for Radar Poetry, which like The Shore, is an online journal of exceptional verse. Rachel Marie Patterson and Dara-Lyn Shrager have a sharp editorial eye for the kind of taut, urgent poetry that responds to the public and private severities of our time.

EF: Please speak to how two poems in this issue of The Shore (not including your own) are in conversation with each other.

KC: I was moved and impressed by so many of the poems in the current issue. Indeed, it seems to me that many of the poems talk to each other. Several are individually in conversation with an intimate second person “you,” who is in some way distant or absent. Some find inventive and persuasive ways to engage political issues. Rilke is probably my favorite poet and it seems the issue is invested with a Rilkean impulse to examine a lost or incomplete self not only in relation to others but in relation to one’s own imagined identity. I found alluring linkages in four poems: Emily Rosko’s “Limerence Ode,” Sarah Horner’s “Asclepias,” Christopher Buckley’s “Profligate” and Sumayya Arshed’s “I’m Sorry I Forgot You after the Funeral.”

These last two seem own a gorgeous threnodic yearning. In Buckley’s deeply affecting, imagistically fluid “Profligate,” the speaker appears to be elegizing himself, as if his life—and perhaps all human life—is vaporous. It seems he’s disappearing before himself. The poem questions the usual primacy people grant themselves. What does the history of a lived life add up to? Buckley answers that “the past is a fine powder / on the road that ends at the sea…”

Moving insightfully back and forth between the settings of the deathbed and the grave on one hand and her own ardent musing on the other, Sumayya Arshed’s “I’m Sorry I Forgot You after the Funeral” is likewise concerned with the insubstantiality of human existence. The intimate “you,” probably an elder, has died and, as much as the speaker wishes to keep hold of the deceased, she can’t: “in the exam room of memory, / i bundle your voice into a fist, and it slips / through my finger.”

I find myself responding to the oceanic sense of loss in both poems.

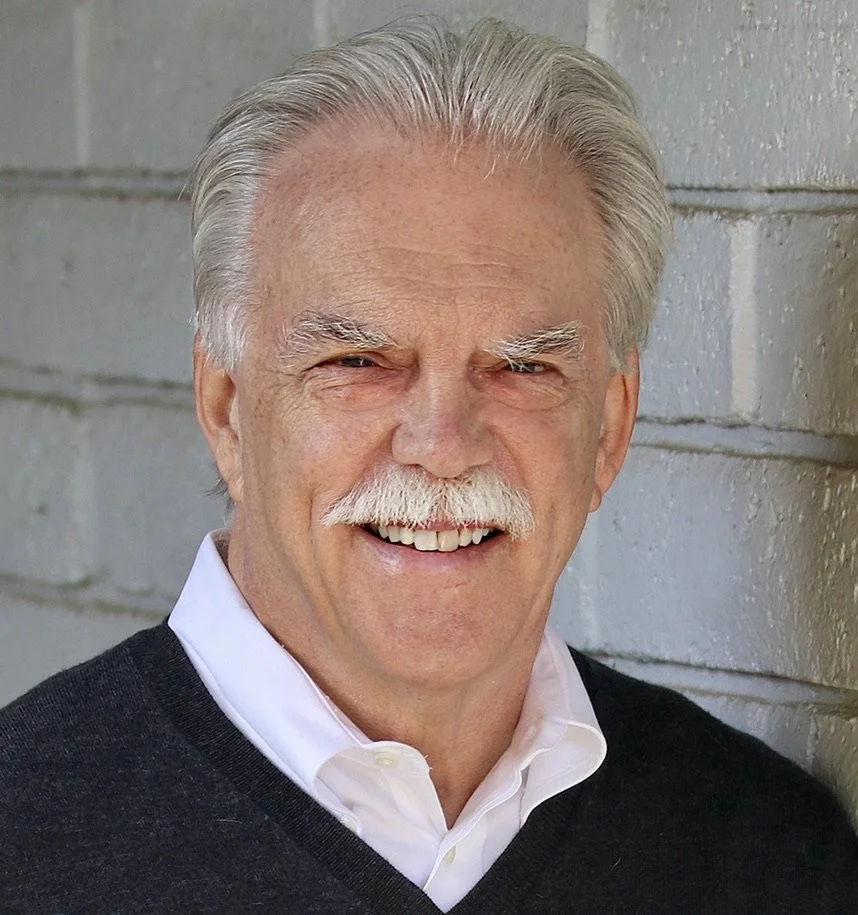

Kevin Clark